The Sketch

Tools to uncover a path

The Sketch

There is a strange paradox at the heart of modern life. We are enamoured with the idea of an analytically ordered society - a society where every decision can be backed up with 'science'. Yet, at the same time, we are deeply distrustful of technology. We are skeptical of the models and methods put forward by scientists, philosophers, and religious leaders. We remain unconvinced that this progress thing was really such a great idea.

This paradox is partly due to different segments of society with different agendas. On one side the technocrats, and on the other the luddites. But you also see it within individuals.

The recent Netflix movie Don’t Look Up is full of such contradictions. The protagonists are scientists whose models identify a threat to earth, earning them the right to be our heroes. Yet at the same time, their hero’s journey ends with them giving up on a scientific approach and focussing on the emotional bonds that really matter.

The problem is that these two positions, in the extreme, are equally harmful.

A society driven entirely by scientific models and hard-nosed calculations lurches from one catastrophe to the next. By replacing reality with reified models, the technocrat ends up with neither reality, nor a good model to rely on1. This is the classic error of mistaking the map for the territory.

At the other end of the spectrum, the luddite fails through a lack of bravery. By being unwilling to put forward an effective model of the world, they lack ambition and the faith in human ability to create the best of what people have to offer. For this person, the models they have encountered have broken so many times that they have learned to distrust all models. In the extreme, this means an unwillingness to stretch what they know now to what they might know in future. This is the error of never drawing a map, or reading someone else’s.

The way forward is achieved by neither of these positions.

We need to work at the edge of the knowledge held in our heads. We need to communicate our knowledge well enough to pursue collective works. And, we need to manage this process so that we do not become tied to the models that we have developed, in neglect of the reality that underlies them.

This is what an effective sketch allows us to do.

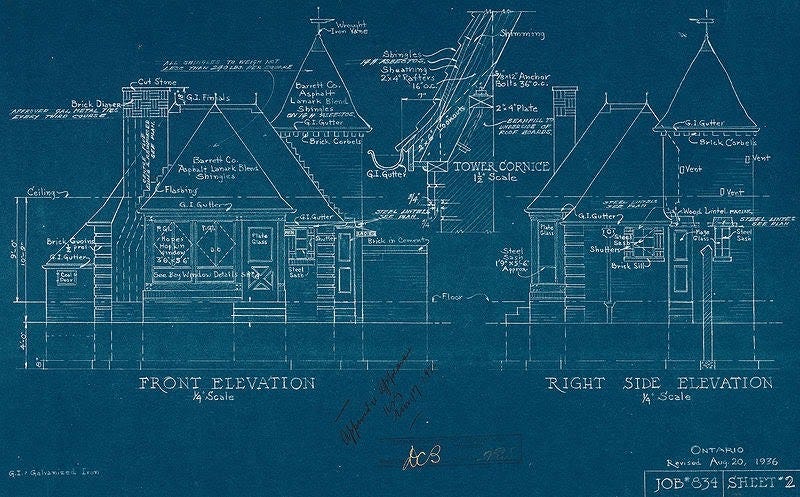

The construction of a house illustrates the challenges that we face, as well as the ways that we can overcome them, without falling too far to one side of this scale.

A house contains more information than you might think. The first order information about physical structure is non-trivial. Simply documenting the number of rooms, the placement of the walls, and the colour of the paint in the library etc. would take reams of paper.

The picture is made yet more complex by second order interactions between components: the quality of light in the hallway at noon, the shine of the tile in the bathroom, or the wood patina that will develop on the floor where the dining room table is placed. Listing these interactions would require a specification at least as long as the US tax code.

More complicated still is the third order information - how these interactions relate to the people that use the house. Are the owners messy or clean? How do they arrange their furniture? Which steps do they consistently skip on the stairs because they creak? When all this complexity is taken into account, it's possible that you wouldn't even be able to write it down.

This situation can feel overwhelming. If it is not possible to document the building accurately through describing lawful properties, then how can we come to terms with it? Nonetheless we manage to create buildings. Investors, owners, architects, and builders - sometimes a single individual acting as all four - navigate these muddy waters to produce real dwellings.

Similar situations are repeated endlessly across the span of human endeavours. A house is a complex thing to build, but even more complex is a company entering a new market, the moon landings, or the creation of a new religious order. These things require the marshalling of ideas, materials and people to interact with a reality that is vastly beyond our capabilities to fully comprehend. In fact the effort seems so superhuman that many people - like those who believe that the moon landings were fake - don't believe that it’s possible. Though, somehow, we keep doing it.

The solution, as experienced by countless building professionals, is that we draw it up. When the construction of the house becomes too complex for us to manage it in our heads, we create sketches.

These sketches do not claim to capture the reality of the house. Instead they act as a compass so everyone involved can navigate the construction. Reviewing a sketch, the future owners can debate and understand how the building may be used. The architect can make explicit the dimensions of each room.The builder can understand which materials to buy and how to put them together to achieve the desired effect. Through the sketch, every party has access to just enough information to form the next phase of their work.

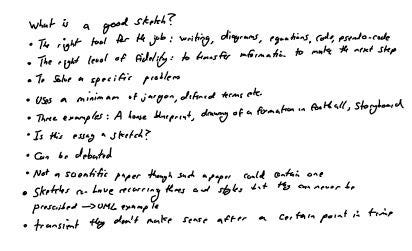

So what constitutes a sketch?

A good sketch solves a specific problem. It is made knowing that, if done right, it can be used to change the world in some way.

A good sketch has the right level of fidelity. It includes just enough information to move to the next step: to make clear what needs to be done, to turn the idea into a shared model, or co-ordinate a group towards collective action.

A good sketch provides enough form to be debated. If there is not enough substance for anyone to disagree then it doesn’t have enough meaningful information.

A good sketch is transient. After the intended action is accomplished, the sketch loses its purpose for anyone except future historians.

A good sketch will be made using the right tool for the job. Sometimes this means words, other times diagrams, equations, code or some combination of these things.

A good sketch uses a minimum of jargon. Though, it is comfortable with a description that could only be understood by a small, well integrated group.

A blueprint for a stove-top espresso machine, a drawing of a football formation, Islamic philosophical marginalia, and a storyboard for a film are all examples of sketches.

A scientific paper is not a sketch. Its formality, precision, and finality prevent it from being part of the kind of process a sketch is produced to enable. However, scientific papers often contain sketches2.

This essay is not a sketch, but this bullet point list that I wrote down in preparation for writing this section is:

With the construction of houses our sketches may have become too precise - bordering on the analytical mode. In the Timeless Way of Building, Christopher Alexander argues just this:

The simple process by which people generate a living building, simply by walking it out, waving their arms, thinking together, placing stakes in the ground, will always touch them deeply.

…

It is a moment when, within the medium of a shared language, they create a common image of their lives together, and experience the union which this common process of creation generates in them.

…

Once the buildings are conceived like this, they can be built, directly, from a few simple marks made in the ground — again within a common language, but directly and without the use of drawings.3

It is true that we are obsessed with technical approaches and overt documentation in our culture, and this manifests with things like how we draft our buildings. We over-complicate, even as we - quite rightly - distrust the process of doing so.

However, we do need the marks. Sketches allow our limited internal capacity to take us from what is to what could be. The next time that you encounter a problem that seems to be of overwhelming magnitude, try sketching a solution.

Thanks to Casey Li for reading a draft of this essay.

Links

The Political & Economic Situation in China

For the last half decade Dan Wang has released an annual letter similar to the one that I sent out earlier this week. His however are beasts, the one for this year clocks in at over 15,000 words. In it he gives both personal and societal commentary on a variety of fronts.

In the first section of the 2021 letter Dan details the current political and economic situation in China. Speaking as an outsider I haven’t seen a better summary anywhere. If you are interested in understanding what life on the ground in China looks like and getting a nuanced take on what the next decade may hold for the country it would be hard to do better than this.

The Origin of Buddhist Statuary

For the first few hundred years of their existence the Buddhist community was an-iconic i.e. they created no direct representations of the Buddha. Instead they opted for symbols like the eight-spoked wheel, the Buddha’s footprint, or the bodhi tree under which Siddhārtha achieved enlightenment. However, following engagement with Grecian outposts in Northern India statues of the Buddha clad in Greco style robes began to appear and indelibly changed the path of Buddhist art. This article does a good job of outlining this history.

How to Build a House to Last

There is a paradox that modern buildings are created with an, at least implicit, expected sell by date. At some point, likely within the next hundred years, they will expire. However, this has not always been the case and there are buildings in use today constructed many hundreds of years ago. This series of posts (I, II, III) from construction physics looks at what it would take to build a building that could survive a thousand years.

For a rich exploration of this process see the classic description of ‘Scientific Forestry’ by James C. Scott in Seeing Like A State

For an example see the great sketch of small world networks on the second page in this classic paper by Duncan Watts & Steven Strogatz

This quote comes from the The Timeless Way of Building, specifically from a set of the italicised headings.