On The Miraculous Life Of The Humble Beaver

Why Canadians should be proud of their national animal 🦫

Since Darwin, evolution has been understood as the selective pressures of an inorganic landscape, plus sexual preference. This results in the survival of the fittest individual organisms and, as a result, their heritable traits. Over long periods of time, this selection process changes the species as a whole. In the hundred years since The Origin of Species was published, little has changed about this structure. We’ve simply recognized genes as the units of heritability.

In recent years though a number of scientists have been building support for an Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) that could modify this story. Under EES, we would greatly enlarge the set of evolutionary mechanisms at play. This includes things like group selection, epigenetics, and niche construction1.

The last of these is particularly interesting. Niche construction happens when “The organism influences its own evolution, by being both the object of natural selection and the creator of the conditions of that selection.”. The beaver is the perfect example of this. Beavers cannot exist apart from the dams that they build, and a similar habitat is not found anywhere in nature if there are not beavers there to create it. Together, the beaver and its dam represent this marvelous steady state of a niche and species where both exist only because of the other.

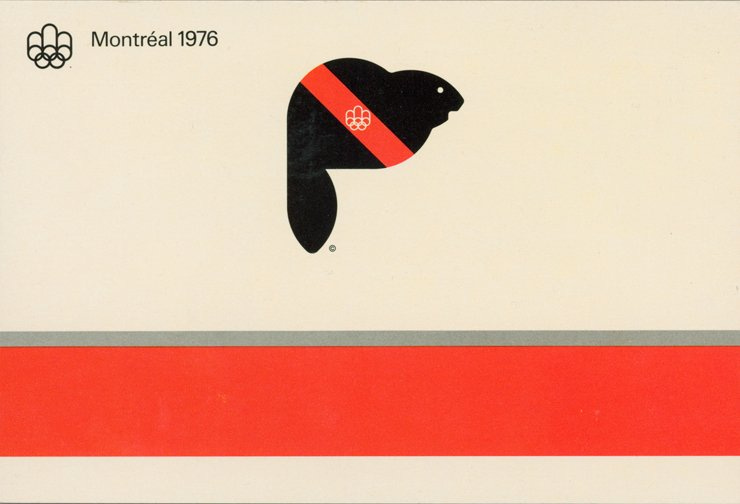

The beaver also happens to be the national animal of Canada. Originally it was chosen for inauspicious reasons. The earliest colonialists saw Canada primarily as a place to take resources from. At the time, no resource was more valuable than beaver pelts. What better way to symbolise the country than using the thing that was most worth plundering2.?

Later, after a few people had decided for some reason that it might actually be worth trying to live there, Northrop Frye identified the Canadian spirit with a "garrison mentality". The country was so inhospitable and so vast that it was impossible to “digest”, either physically or mentally. Confronted by the terror of this unfathomable wilderness, Canadians retreat to the safety of community and small 'c' conservatism. The energy of the culture is put to work as best it can with building the walls of its fort to keep the nature out. As Frye put it:

The impressive achievements of such a society are likely to be technological. It is in the inarticulate part of communication, railways and bridges and canals and highways, that Canada, one of whose symbols is the taciturn beaver, has shown its real strength.

Canadians live in a country that has no interest in their being. As a result the people have a sense that they need to constantly carve and arrange the country to suit them both economically and culturally. In line with this, Canada is also perhaps defined by immigration more than any other nation in history3. It is a country that was chosen by people creating a particular kind of life, rather than by an ethnic or cultural tradition stretching through the generations4.

In all, this means it is a place defined by high agency and creativity. But it also means that life is precarious. You are hit in the face with the economic fragility as soon as you step outside of the house in January and there is a constant crisis of Canadian ‘identity’, whatever that means.

Luckily, the beaver is a creature that does not take itself too seriously. As national animals go, it’s pretty silly. The US has the magnificent eagle, surveying its kingdom. Thailand has the elephant, wise and prosperous. India, the tiger; strong, cunning, and fiercely independent.

The beaver is rotund and taciturn. At best you might say that he’s good with his hands. But he's also kind of cute and maybe a bit cheeky. A fish out of water that somehow manages to make it work.

Canadians may sometimes be patriotic, but we have a general aversion and distrust of nationalism. On one hand this is surely because it’s a very liberal place; but on the other it is also because it would be an incredible LARP. The country has always been a sideshow to vast empires, first as a colony of Britain then as an important but still relatively small trading partner to their closest neighbour, the United States. Claiming some kind of grand narrative or an idea like manifest destiny in the face of these comparisons would be a little juvenile. A slightly cute and whimsical self-denigration may be just the ticket.

The beaver is a miracle. A creature that, through persistence and ingenuity, has been able to mould an inhospitable environment into a unique home all without taking itself too seriously. Canadians should be proud of their national animal.

Thanks to Casey Li for reading a draft of this essay

Links

Paper Belt On Fire

I recently finished Michael Gibson’s book Paper Belt On Fire. Michael was the lead for grant distribution for the Thiel Fellowship and is now the founder and general partner of the 1517 fund.

It’s one of those hard to classify works that mixes autobiography, philosophy, history and a touch of political rhetoric. At the end I came away inspired to go promote some human agency and with a solid grasp on a vibe that could power the regeneration of our culture and our institutions. There’s a wonderful summary of some of the ideas in the book in this discussion.

Check out this gorgeous thread of art posted a couple of days ago to celebrate the Winter solstice:

If you are interested in the future of biology, this work is worth paying attention to. The fundamental Darwinian insight is sound. Yet, there is much we don’t know about how life changes across time. Some ideas, like the universality of self-organisation of matter and mild forms of entelechy that provision the abundance of species that we see are radical. Though, no more radical than quantum mechanics was in relation to classical physics.

This extractive view meant that the beaver almost became extinct at one point. Luckily conservation efforts have meant the population is thankfully once again very healthy.

For reference, in 2018 first generation immigrants made up 13.8% of the US population and 22% of the Canadian population.

As a sidenote, I am forever a little disappointed with the national anthem 'O Canada' for its use of the idea of “native land” in one of the first lines. It simply doesn't ring true for a place where a quarter of the population chose to move there. It’s not quite anthem materials but I agree with Stephen Harper that Northwest Passage by Stan Rogers feels more appropriate for capturing the spirit of the place.