Happy New Year to all! I hope that everyone has had a good holiday season and is ready for 2021. I am hopeful that it will bring good things for us 🙏

I loved the process of writing for this newsletter in 2020. However, I didn’t create quite as much as I would have liked. I am also a strong believer in the idea that commitments can breed positive things beyond their initial scope. So, for 2021 I’m committing to sending one newsletter a week on Saturday mornings. The email will have one short essay (probably 500 - 1000 words) and one book review. The pieces below are indicative of the kind of content. Though, hopefully the quality will get better with time!

Depending on how much time I have I may also post other longer pieces intermittently. Either way you can expect to see this domain appear in your inbox more often.

Essay: Beliefs as Emergent Realities

An emergent structure is a reality composed of simple sub-systems but not reducible to them. A home is such an emergent structure. A home is composed of land, walls, windows, ceilings, furniture, and heirlooms. Yet, it is only when all of these things work as a whole that we call it a home. Further, when these pieces are all brought together only the designation "home" will do to describe that collection.

This is an important idea. While it is usually not front of mind, emergence like this is critical to how we do science and understand the world more broadly. In a scientific paradigm, a reductionist world view eventually reduces everything down to the level of atoms and fundamental physics laws. The general idea is sound, these physics laws do constrain the possible space of the world. However, it is not enough. The realities of physics cannot be used to predict a priori the realities of chemistry that have been discovered. The chemical macrolaws governing the composition and transition of molecules and states constitute some of our most profound scientific discoveries with a multitude of applications. While the subsystems for these laws are those physics principles the laws themselves are emergent from the underlying physics in a non-reducible manner.

The beliefs we hold, just like the laws that govern the interactions of molecules, are emergent. There are many things that can go into forming a belief. Sources include economic incentives, psychological habits, rational investigations, cultural heritages, and biological structures. Like with the example of the home, while all of these may play a part in the development of a belief no belief is fully reducible to any collection of them.

Buddhism first appeared in the North East of the Indian sub-continent in the vicinity of modern day Nepal at the height of the axial age ~400 BCE. From this beginnings the tradition developed for hundreds of years before migrating via the silk road into the Chinese state. Sometime during the Sui (581 - 618 CE) and early Tang (618 - 907) dynasties the tradition found its sea legs and developed rich new religious centres and innovations that went on to inspire and inform massive cultural productions and intellectual development first across East Asia and now the world.

A core tenet of Buddhism since its foundational moments has been that all life is sacred and a monk should never harm other beings. Such a principle, especially in this kind of strict form if considered on its own poses a problem of how one should eat. How do you avoid harm when consuming other living things? In India this issue was resolved by the nature of the begging bowl. If a monk received a particular kind of food in the bowl, whether meat, animal product, or vegetable they would eat it. In this case, the only thing worse than the original harm to a creature would be to waste the resulting meal.

A culture of asceticism in harmony with villager life to support such a practice was well developed in the areas where Buddhism was first flourishing. This meant that the monks always had a ready supply of food available.

However, no such culture of asceticism or giving existed in China. So, upon translation to the Chinese surroundings the monastic community was suddenly faced with the question of how they would eat and what they would consume. To resolve this the community came up with a set of innovations. The most important was that the monks learned to farm as part of their regular religious duties. Monasteries started to create intricately run agricultural communes, sometimes very large spanning many acres.

While this setup mostly resolved the economic reality of the food supply the issue of what to eat was no less pressing. The beliefs that the monks had taken on surrounding non-violence and karma meant that they had to carefully determine what they would consume. Raising animals to kill them was out of the question and likewise there were dangers associated with pulling up or doing unnecessary damage to any plants. So, in China Buddhism became a vegetarian religion with very particular rules about where and how their vegetables should be harvested.

This story shows how we should think about beliefs. Of course, a belief lives in the world. Every belief must navigate a course through ecosystems of psychology, economics and the rest. Yet, no belief is reducible to these systems, when looking at how beliefs operate we must treat them as emergent structures with their own ontological reality. The behaviour of the monastic communities changed to respond to a new cultural and economic climate and the belief in a non-violent existence played a determining role in those changes.

📘 Book Review: Zero to One

These are my notes from my second reading of Zero to One: Notes on Startups or How to build the Future. The first time I read the book, I believe around 2015, I had little background on Peter Thiel's views. I also had less grounding myself in exactly what a company is. I had never worked at one at that point so it was really all theoretical.

I have seen the book sometimes marketed on book stands in airports along with the pop business books. I don’t think this does it justice. Most of these books follow a hackneyed approach. They tell you what they have to say (usually a kind of simple practical wisdom) in the introductory ten pages and follow up with 200 pages of anecdotal stories as 'proof'. Like these books there is a core thesis to Zero to One but every chapter has new theoretical additions and points of argument. I have a bullet point list of some key useful heuristics a little later that shows this range. Despite this complexity, after this second reading, I think I can sum-up my main takeaway from the book in one sentence: A successful startup is a cult that got their vision of the future right.

To illustrate this we can start with one of the standout mental models from the book that describes a quadrapartite division of ways to imagine the future.

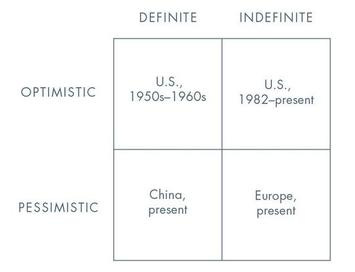

When thinking about what will be you can either believe that you are able to shape how that future will look through your actions or that you will not (Thiel terms this having a 'definite' or 'indefinite' view). You can also believe the future will be better than the present (optimistic) or worse (pessimistic).

There is a great discussion in the book of the four different views that come from combining these modalities. They are mapped onto countries, philosophers, and financial systems each making for interesting, if contentious, reading. The punchline is that there is one view of the future that rises above the rest Optimistic Determinism: The world will be better tomorrow then it was today and we can make it so.

The ultimate expression of the optimistic determinist view is a speech in 1962 stating "we choose to go to the moon in this decade" followed by a successful moon landing in 1969. This kind of posture, Thiel maintains, is the one that every successful startup needs to have.

Later in the book there is an illuminating story that shows how this works in practice. It contrasts the slew of 'cleantech' companies that were founded in the early 2000's and Tesla. There were many things that cleantech did wrong and Tesla did right. However, one of the key reasons for the failure of the former is that they didn't have a plan for the future.

As Thiel tells it, the cleantech giants were founded on a kind of optimistic hope that now was “the time” for clean energy. In the rush to capitalise on this ‘time’ they received vast sums of venture capital funding and government support. Yet all the while they lacked a clear idea of what they needed to do technically to build new clean energy solution or how they would market those solutions if they did develop them. The companies floundered and eventually went bust. Tesla on the other hand was deliberate at ever turn to develop a plan first to have a fully electric car that worked well enough to be used, second to make that car cool leveraging a real social desire to reduce pollution. Both goals that it has since achieved, accelerating the worlds transition to sustainable energy.

So, a successful startup needs to have a positive and definite vision of the future. As an additional layer to this, the vision should be bold. If it isn't bold enough it won't be able to motivate the leap that creates big changes in human capabilities. Thiel terms these changes 0 to 1 moves - which give the book it’s name - and characterises them as the ultimate measure of human progress. It is new and unique creations (0 to 1) rather than their reproduction (characterised as 1 to n change) that changes the world for the better and offers the greatest possibility of a bright future. For me the kinds of things that live in this space are the emergence of the Confucian emphasis on humanity above all else; the flying buttress and pointed arch giving rise to the cathedral; the results of the Philadelphia constitutional convention; and the development of the world wide web. These are the kinds of things that change the trajectory of the world. So, we should make big plans.

To pursue such a vision, given you will most likely fail, you need to be at least a little crazy. Additionally you will need multiple people working in very close alignment as only teams can get big things done. As the book defines it, this is a startup: The maximally large working collection of people with a shared, bold vision of the future working as hard as they can to make it a reality. To take that final step and actually succeed, you need to be right. Hence a successful startup is a cult that got their vision of the future right.

In no particular order here are some other useful heuristics from the book:

All successful companies are monopolies. This is micro-economics 101 but Thiel observes that everybody, due to regulatory oversight and corporate equivocation is confused about it in practice. When you are first starting you should aim to find the smallest viable market you can monopolise and expand from there.

It’s a truism that almost all of the returns for VC's are dominated by the 10x to 1000x companies. Following from this, given the assumption that value is created through 0 to 1 change, successful startups need to develop at least 10x better technology to be breakout successful - for clarity this ‘technology‘ can be multi-dimensional, a new way of doing sales is as much a technology as better server formatting.

Distribution is just as important as 'product'. Different types of company have different types of distribution needs from enterprise sales to mass social media marketing but no matter the mechanism you need to be able to convince your customers of your vision for the future if they are going to buy your product. No product sells itself.

Machines on their own while they may be very fast and efficient are, at least for now, only capable of 1 to n change. The most successful technology startups will enable more people to make 0 to 1 type changes.

Profound changes come about from "secrets" that are only available to a few. A secret is a type of knowledge that lies on a spectrum halfway between conventions and mysteries. In comparison to a convention a secret is hard to discover but unlike a mystery it is not impossible. With a secret one gains leverage. Most great startups (and for that matter cults) have a secret, or several, that they use to enact their vision of the future. Most secrets are in fact already out in the open available for anyone who is willing to look.

Taken in totality the book feels like a rallying cry. Let’s build the future together.